Grady Booch, one of the genuine elders of the software engineering discipline1, recently did a two-hour conversation with Gergely Orosz on the Pragmatic Engineer podcast. The whole thing is worth listening to, but one thing that particularly struck me was the way Booch described the discipline of software engineering:

Ours is a field that tries to build reasonably optimal solutions...that balances the static and dynamic forces around them much like what structural electrical chemical engineers do. In the software world, of course, we deal with the medium that is extraordinarily fungible and elastic and fluid and yet we still have the same kinds of forces upon us.

Hearing this made me realize that my mental model of "software engineering" really had kind of become "person who writes code." Booch's description broke that frame immediately. A software engineer is doing the same kind of work as a structural engineer distributing load across a bridge or a chemical engineer balancing reaction rates and heat dissipation in a lab. You balance competing forces (performance vs. maintainability, speed-to-market vs. reliability, user needs vs. technical constraints) into something that works for its intended use. That's a great mental model of what engineering is – software or otherwise.

That framing made me think about claims that AI is going to replace software engineers much more skeptically.

Software "engineering"

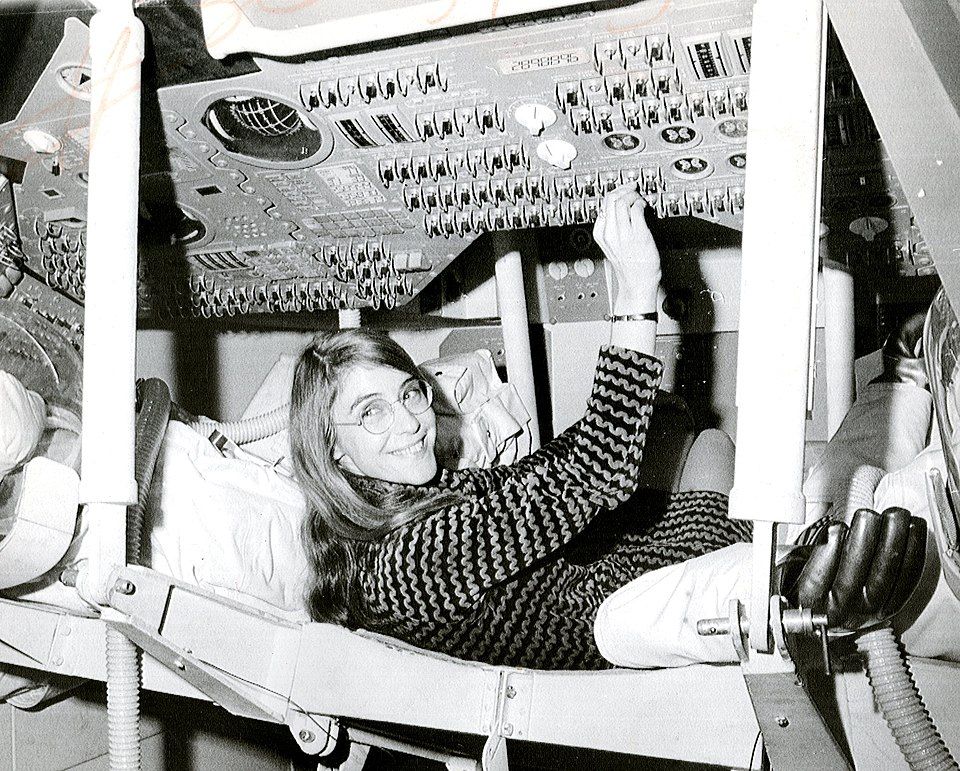

Booch credits Margaret Hamilton as the first person to call it "software engineering." She was working on Apollo2, "one of the very few people who were software developers in a sea of mostly men who were the hardware structural engineers," and she wanted a title that said what I do is engineering too. So she called herself a software engineer:

I fought to bring the software legitimacy so that it—and those building it—would be given its due respect and thus I began to use the term 'software engineering' to distinguish it from hardware and other kinds of engineering, yet treat each type of engineering as part of the overall systems engineering process. When I first started using this phrase, it was considered to be quite amusing. It was an ongoing joke for a long time. They liked to kid me about my radical ideas. Software eventually and necessarily gained the same respect as any other discipline.

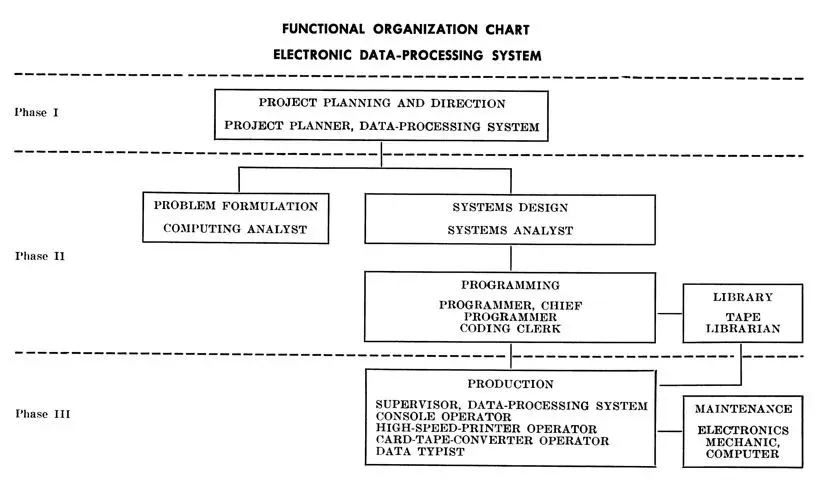

Whatever laughs Hamilton's term got, it was plausible enough. At the time, software engineering genuinely wasn't coding. Booch describes an explicit division of labor – the thinking and the typing were literally different jobs.

You had people who had analyzed the system, people who would then program it, people who would key punch the solutions, people who would operate the computers.

As early as 1947, von Neumann and Goldstine's Planning and Coding of Problems for an Electronic Computing Instrument laid out a formal hierarchy of stages, with the mathematical and logical planning on top, and noted that:

Coding is, of course, preceded by a mathematical stage of preparations. The mathematical or mathematical physical process of understanding the problem, of deciding with what assumptions and what idealizations it is to be cast into equations and conditions, is the first step...It should be noted that the first step has nothing to do with computing or with machines: It is equally necessary in any effort in mathematics or applied mathematics. Furthermore, the second step has, at least, nothing to do with mechanization: It would be equally necessary if the problems were to be computed "by hand."

By 1959, the Department of Labor's survey of computing occupations formally distinguished between systems analysts, programmers, and coding clerks as separate jobs.

The Cold War helped keep the momentum up. At a time when it was otherwise hard to find funding for computery things, the defense establishment couldn't throw money at it fast enough, and governments throwing money at things like to make them sound official. What could be more official than a NATO conference?

The idea for the first NATO Software Engineering Conference – and, in particular, the idea of adopting the then practically unknown term software engineering as its deliberately provocative title...

And it became clear during the conference that the organizers had a hidden agenda, namely, that of persuading NATO to fund the setting up of an International Software Engineering Institute...

It was little surprise to any of the participants in the Rome conference that no attempt was made to continue the NATO conference series, but the software engineering bandwagon began to roll as many people started to use the term to describe their work.

— Brian Randell, Memories of the NATO Software Engineering Conferences, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 01/01/1998.

In the early days of computing, there was both a self-conscious attempt to tuck software-making under the umbrella of "engineering," and an operational separation between the work of conceiving and architecting software and the work of physically making it.

The software crisis

At the same time as the software engineers were running around Garmisch and Rome giving themselves cool NATO titles, they were also facing an emerging problem: the software crisis. (cue dramatic music)

The basic problem is that certain classes of systems are placing demands on us which are beyond our capabilities and our theories and methods of design and production at this time. There are many areas where there is no such thing as a crisis — sort routines, payroll applications, for example. It is large systems that are encountering great difficulties. We should not expect the production of such systems to be easy.

Kenneth Kolence, quoted in SOFTWARE ENGINEERING: Report on a conference sponsored by the NATO SCIENCE COMMITTEE Garmisch, Germany, 7th to 11th October 1968

Computers were becoming advanced and important enough to do stuff that we knew we could do with computers (including "beat the Soviets!"), but we did not have enough of the right people with the right knowledge to actually do those things consistently or well or at scale.

This problem got approximately a billion times worse as personal computers happened. Demand for software went from "a lot" to "literally insatiable" at the same time as the tools for making software became relatively much more accessible. When you can't hire fast enough, you hire for the bottleneck, and the bottleneck was code output. So "software engineer" drifted into meaning "person who types code on a keyboard."

Ask most people today what a software engineer does all day and they'll say "writes code," which is kind of like saying an architect "draws lines." The engineering part—the force-balancing, the systems thinking—got swallowed by its most visible output.

The software un-crisis

I was recently vibe-coding an app with my buddy Patrick. Patrick is a professional software engineer. While it's true that we both were generating code, the yawning chasm in both speed and quality between his work and mine was unmistakable. When Copilot would review our PRs, he knew which feedback to incorporate and which to ignore; I was clicking basically at random. His commits always came with test coverage, because he had instructed his agents to work that way; mine came with messages like "jfc please work this time" or "I hate typescript." He orchestrated his group of agentic coders like a scrum team, and was thoughtful about how and in what order to unleash them for maximum throughput and optimal architecture; I was on a one-lane highway in my VSCode sidebar, trapped behind my own ignorance as it did 30 in a 65. I could prototype my idea, but I could not make it a functioning, scalable web application. I couldn't balance the forces.

Scale the me-Patrick dichotomy up to civilizational scale, and you can see what's actually happening here: By enabling anyone to become a coder but only good engineers to make really good software, AI is re-establishing the distinction between the two practices. AI is reversing the software crisis dynamic.

We collapsed engineering and coding into one job to maximize throughput and solve a code scarcity. AI coding agents have made code output effectively infinite. They're trained on problems we've seen solved over and over, and they're great at accelerating known patterns, so they're very good at the coding part of software engineering and not great at the engineering part.

What this means in practice is that different kinds of developers are going to have very different experiences over the next ten years3:

-

People who love the architecture but hate the scut work are about to feel like they have a superpower. You think carefully about tradeoffs, you define best-practice architectures, you create a scalable infrastructure—and then you spend three hours trying to figure out what that one 80-line-long function in app.tsx is actually even doing. AI is vaporizing that part of your job. You're free. Less typing, more engineering.

-

People who love churning out code but don't really want to engage the bigger questions are going to feel squeezed. If the flow state of writing code and the whoosh of Jira tickets moving to the right as nobody bothers you is the part you love, and you'd rather not think about architecture or tradeoffs or organizational dynamics, then you're gonna have a bad time. AI is automating the part of the job that gives you energy.

Booch, for what it's worth, frames AI coding assistants as part of a general trend through the history of computing towards higher and higher levels of abstraction.4 This feels like the right way to think about it. AI coding isn't something new, but something that's finally reaching a high enough level of abstraction to re-establish the distinction between software engineering and coding that defined the field until the software crisis collapsed them into one thing and we forgot they'd ever been separate. The division of labor is back, except this time the room full of people who type your software into the computer are an array of TPUs somewhere in the Sonoran desert. It's valid to worry that this is disruptive/unsustainable/environmentally problematic, and you certainly don't have to think it's a good thing. But I don't think we should fool ourselves into thinking it's new.

I haven't asked her, but I bet Margaret Hamilton feels right at home bossing Claude around.

Footnotes

He literally has a gray beard! ↩︎

"What does your app do? Oh wow, you can order food from local restaurants? That's neat. Oh mine? Not much, it just GOES TO THE LITERAL FREAKING MOON." ↩︎

Or months! Or weeks! ↩︎

Booch describes each golden age as a step up in abstraction: first we abstracted algorithms (formula translation, programming languages), then we abstracted structure (object-oriented design, combining data and processes), then we abstracted infrastructure (the internet, libraries, platforms). AI coding assistants are, in his view, the next rung on that same ladder. ↩︎